In this day and age, when evidence of how divided our country is can be found just by turning on any one of the multiple 24-hour news channels, do we really need a fictionalized cautionary tale of how bad things can get?

Not really.

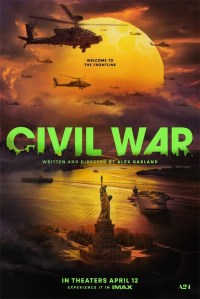

But Alex Garland’s dystopian new film Civil War is exactly that. It plops us right into the middle of a United States where all the dire predictions we’ve been hearing about for years on CNN, Fox News, and the rest have come true. It’s not a pretty sight. But it is a pretty great movie.

Set in an unspecified not-too-distant future, the film is about the chaos of war. And I do mean chaos. For starters, there are not two but four warring factions: the “Western Forces” of California and Texas; the “Florida Alliance;” the “New People’s Army,” based in the Pacific Northwest; and the “Loyalist States.”

It’s not exactly clear why everyone is fighting or what each group is fighting for. We don’t get a preamble or much of an explanation. Everyone just appears to be angry and fighting with each other. As one soldier says, “Someone’s trying to kill us, and we’re trying to kill them.”

In the middle of all this is a group of journalists (played by Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura, Stephen McKinley Henderson, and Cailee Spaeny — who looks nothing like she did in last year’s Priscilla, by the way) who head out on a road trip from New York City to Washington, D.C., hoping to interview the President (Nick Offerman) before members of the Western Alliance kill him.

The film generally attempts to avoid the specifics of contemporary politics and can be applauded for not taking the obvious route of making the war here one between red states and blue states. Which raises the question: What could possibly unite California and Texas and lead those states to fight together? We never find out.

That said, we do know the President is something of a dictator who is on his third term, and that he’s abolished the FBI. Blustery proclamations like “Some are already calling it the greatest victory in the history of mankind” are one clue to the real-world inspirations behind this fictional conflict, as is a reference another character makes to an “Antifa massacre.” So, there’s that.

But centering the film around this group of supposedly objective journalists instead of the combatants allows us to avoid taking sides. The on-screen administration does consider journalists to be the enemy, but the quartet is heading to the capital not to take the President down themselves. Rather, they want to get there before the White House falls simply because it’ll make for a good story. And this turns Civil War from a war film into one about what it takes to document the horror of war. We don’t care who wins as much as we wonder who’ll survive.

As Lee, a veteran photographer, Dunst gives one of her better performances, capturing the fearlessness and detachment necessary to succeed on the job. Likewise, Moura effectively portrays his character’s seeming indifference to the proceedings. And Henderson does predictably good work as the elder statesman of the bunch.

Spaeny’s Jessie is essentially our audience surrogate, guiding us through the chaos and showing us how someone comes out the other end. Early on, we watch the action through her eyes. But as the movie goes on, we see how Lee’s reluctant tutelage of Jessie turns her into the kind of cold and unfeeling journalist Lee is — the kind necessary to succeed in her profession, and one that will take Jessie far. Spaeny’s impressive portrayal of Jessie’s lost idealism is one of the darkest elements of the film.

Civil War is incredibly well shot (kudos to cinematographer Rob Hardy, who previously worked with Garland on Ex Machina and Annihilation), and its authenticity is no doubt due to the contributions of military supervisor Ray Mendoza. It also uses a handful of great, unexpected needle-drops to set the tone and give an extra jolt to the proceedings.

Like any road-trip movie, Civil War does have an episodic quality to it as the journalists encounter fighters, colleagues, and other folks along the way. Danger lurks nearly everywhere. In one particularly unnerving scene, Jesse Plemons (Dunst’s real-life husband), plays a kind of deranged white supremacist who asks the group what kind of Americans they are. Those whose answer he doesn’t like get shot and added to a mass grave.

And then the film culminates in a loud, extremely violent battle in D.C., in which — well, I’m not going to ruin it. But suffice it to say, the sequence puts us right in the center of the action and leaves us with a lasting impression of just how bad things could get.

About halfway through the film, the journalists come upon a small town where a local shopkeeper is pretending like there’s nothing going on outside her door. It’s a nice sentiment, and back here in the real world, it would be nice if that were possible. Alas, in recent years, we’ve already been given a preview of what may be coming if people feel even more divorced from where this country is headed (and from reality, to put it bluntly). Ignoring it won’t make it go away.

Civil War is obviously not real, and I’m not a fatalist, but if things continue down the path we’re on, it may not be all that far from the truth. And yet, in spite of that, I enjoyed this movie very much.

I’m giving it a B+.

3 Responses to “Documenting a Civil War that Isn’t Real. Yet.”